The Cowan brothers:

Charles standing, Ken seated at right

(with younger brother Arthur seated at left)

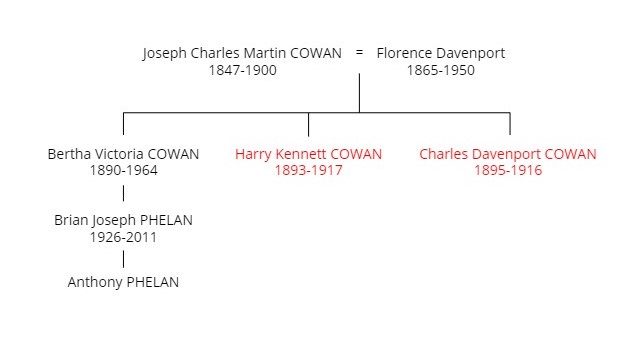

One of the interesting parts of my journey in family history research has been discovering the many men in our family who served in the Great War. Dad in fact had uncles on the Phelan side who served that he himself didn't recall. But there were another two who were definitely remembered: Ken and Charles Cowan were the two eldest sons of Joseph Charles Martin Cowan and Florence Davenport, and would also have been Dad's uncles were it not for the fact that both were killed in the horrific conflict. Ken and Charles were among the first men to sign up in support of the empire. On 11 August 1914, just one week after the declaration of war, the call went out for volunteers in Australia. Four days later, on 15 August, both boys showed up to heed that call, Ken enlisting at Melbourne and Charles at Moonee Ponds.

Harry Kennett (Ken) Cowan was 20 years old, had been working as a grocer and playing football. He had done two and a half years' compulsory military service in the 52nd Infantry Battalion (Scottish Regiment). He was assigned as a Private to the 5th Battalion of the newly-raised Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Charles Davenport Cowan was just 18 and was a Clerk in the Water Commission Office. His service had been two years in the Senior Cadets and one year as Sergeant in the 58th Infantry Battalion (Essendon Rifles). He was assigned to the 7th Battalion, under the command of Harold 'Pompey' Elliot, his commander from the Essendon Rifles. Charles' previous experience saw him enter the force as Lance Corporal. Both battalions formed part of the AIF's 2nd Brigade, 1st Division.

Usually when researching servicemen in the Great War I would find their service number had at least four digits. Ken and Charles' numbers indicate just how quickly they had volunteered: Ken's was 14 and Charles' 415.

Crowds came out to cheer these new recruits on 19 August as they marched out from Victoria Barracks to the newly-created training camp at Broadmeadows. After two months of preparation there (with musketry training at the Williamstown Rifle Range), the forces were ready for departure. On 18 October they boarded trains for Port Melbourne, where the next day Charles embarked on the Hororata, Ken following on the 21st on the Orvieto (the last of 16 ships to depart Melbourne)*. By 25 October both ships were in Albany where they waited for the whole Australian fleet of 36 troop ships to assemble before all sailed out on 1 November. A few days later the Sydney diverted to incapacitate the German ship Emden, ensuring the fleet a safe passage. On 28 November the troops received word that they would be based in near Cairo in Egypt for training and not in England as first thought. Soon they were through the Suez Canal and on to Alexandria, arriving 5 December. The following day they travelled through Cairo to their camp at Mena.

Christmas was spent in Egypt, with these young Australian men no doubt wide-eyed as they experienced the bustle of Cairo and the grandeur of the Pyramids on days when they were freed from their rigorous training. There was some excitement in early February as the 7th battalion was sent to Ismailia to help in defense of the Suez Canal, though by the time they were there the Turks had already been pushed back so there was no action to speak of. Finally, on 3 April 1915 word came through that the Australians would be off to their first true theatre of war: the Dardanelles. Ken's battalion sailed from Alexandria on the 6th, Charles' on the 8th, for the island of Lemnos in the north Aegean Sea. There they would be readied for the fateful attack on Gallipoli.

On the morning of 25 April, the troops were transported on ships under cover of darkness, and the first rowboats were sent out to shore before dawn. It was supposed to be a surprise raid but the Turks were ready. The 5th and 7th battalions were part of the second wave onto the beach, so had to wait for the return of the rowboats from the first wave. Imagine what these young men were thinking as they saw casualties returning in the rowboats ahead of their turn. But off they went, and amongst the shrapnel, rifle and machine gun fire, Charles was wounded before his boat had even landed. In fact he had quite a miraculous escape, his tunic being 'shot almost to ribbons by a machine gun' with one bullet going through his right cheek and another through his left ear (according to a newspaper account, though his war file reports this as 'slight scratches' to the face!). He was immediately sent back to hospital in Egypt.

Ken made it through the landing unscathed and into battle. On 1 May he was able to 'enjoy' two days of respite, at which time he received a promotion to Corporal. On the 6th the whole 2nd Brigade was moved by ship to the southern tip of the peninsula where on 8 May they advanced on Ottoman positions in what was known as the Second Battle of Krithia. There were heavy casualties, and this time it was Ken's turn, suffering a gunshot wound to his left hand, eventually being sent to a hospital in Malta.

By late May Charles had recovered and on the 28th left Alexandria to return to Gallipoli, where he rejoined his 7th battalion on the 4 June and was promoted to Sergeant the following day. The battalion was positioned in the relative safety of dugouts, but suffered periodic shelling. On 3 July they were in the action again at Steeles Post where they had to deal with snipers and howitzer fire for over two weeks. After a two week break they learnt they would be in reserve for the attack at Lone Pine. Orders came through on 8 August to relieve the 1st & 2nd battalions, whence they came under heavy attack. While the battle was a success, overall the situation at Gallipoli was still much of a stalemate, and for over a month the battalion went through a cycle of being brought into action and then relieved while there at Lone Pine. Finally respite arrived as the battalion was sent back to Lemnos to recover on 12 September. Incredibly four Victoria Crosses were awarded from this stint for the 7th.

Meanwhile Ken, recovering from his injuries, was transferred to Egypt in August before rejoining the 5th battalion at Lemnos on 9 September, the same day it had arrived there for a break from the hostilities on the Peninsula. Perhaps the brothers had a chance to reconnect when Charles' 7th joined them shortly after, however it is possible this might not have occurred as Ken was hit with the flu, and hospitalised on 15 September. It appears that he remained unwell for many weeks and on 25 November was sent from Lemnos to England with enteric fever (typhoid). This kept him out of action for many months, spending nearly three months in hospital from December 1915 to February 1916. By the time the 7th Battalion was sent back to Gallipoli, Charles was suffering jaundice and was himself sent to hospital in Lemnos on 3 November; he would not return to his unit until Christmas Eve, meaning that both brothers missed the successful evacuation of troops from the Gallipoli Peninsula that was completed on 20 December.

On 4 January 1916 Charles and the rest of the Australian troops left Lemnos and returned to Egypt, where they were based at Tel el Kebir, then Serapeum. The forces needed to be reorganised after so many casualties were sustained at Gallipoli, and on 15 February it was announced that battalions would be split in two, with reinforcements added to each to ensure an even spread of experience. The 7th lost their beloved leader 'Pompey' Elliot at this stage, as he was promoted to the command of the 1st Brigade. Training continued until 25 March, when the troops were moved out for Alexandria in preparation for their next phase of action: France and the Western Front. Arriving at Marseilles on 31 March, the Australians had three days of train travel to the north of France, where they were billeted at La Creche. April was spent training in preparation for action on the French battlefields.

On 28 April orders came through that Charles' battalion (the 7th) would be supporting the 5th. Billeted at Fleurbaix, the 7th suffered an early barrage of shelling but it was generally regarded as a quiet sector. Work was carried out digging communication trenches, repairing other trenches and laying wire. On 9 June, the 7th was moved to Sailly where they laid cables, but were soon on the move again, arriving on the front lines at Ploegsteert on 24 June to relieve the 3rd battalion. From 4 July they were constantly on the move, either marching or on trains, to locations where they served as support to other battalions. On 21 July the battalion was at Albert and getting ready for their first major offensive since Lone Pine while Charles was sent to England to undertake officer training. He would miss the attack - the start of the infamous Battle of Pozieres.

Meanwhile Ken was over his bout of enteric fever, and arrived back in France on 3 August 1916, probably rejoining his 5th battalion while it was resting at Bonneville following intense fighting at Pozieres. From 7 August the battalion was on the move ending up in La Boiselle on the 14th and the following day taking up positions in the trenches at 'Death Valley' in readiness for their attack in the Battle of Mouquet Farm (also known as the '2nd Battle of Pozieres'). Following his officer training Charles was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant on 5 August and back with the 7th battalion on the 17th. On this day the battalion was being briefed on their upcoming attack in the same battle (overall, nine attacks were made by three divisions of Australian troops over four weeks without success, at a terribly heavy price of 11,000 casualties).

On 21 August both the 5th and the 7th battalions were relieved and gained much needed rest at Warloy: perhaps this was a chance for the brothers to have decent contact with each other for the first time in a while. Then for both battalions another period of marches and train transport to various billets and camps beckoned, ending in Belgium at Poperinghe on 29 August. The following day the 7th moved into trenches in the Bluff sector at Ypres. Fortunately this sector was relatively quiet after the mayhem at Pozieres, and their days were spent repairing trenches until relieved on 12 September. From that time the 7th contributed work parties in the region as required. Meanwhile the 5th also formed work parties before their turn on the front lines came on 13 September where they stayed for two weeks.

On 20 September the 7th was advised that they were to provide a raiding party in the Hollebeke area. Their aim was to follow an artillery and mortar barrage with a dash to parapets to cut any wire obstacles. Charles Cowan was the officer who led a reconnaissance 'wire party' on 29 September, in which he laid a phone line back to headquarters, and then excelled during the raid itself the following evening. The raid was a great success and Charles was "mentioned in dispatches" for his efforts and recommended for the Military Cross:

At Hollebeke on the night of the 29th September and again on the 30th September 1916, during a silent raid on the enemy trench, 2nd Lieut. C. D. Cowan, who was in charge of the wiring squad of the Raiding Party, displayed great bravery. On the night prior to the raid he carried out valuable reconnaissance of 'No Mans Land', where the trenches were only 40 yards apart, reconnoiting the ground within 10 yards of enemy's parapet at a great personal risk. On the 30th, the night of the raid, 2nd Lieut. Cowan, accompanied by 50 O.Rs was responsible for the direction of the party and the improvement of the gap in wire. When within 10 yards of enemy's front line, he rushed his men at the enemy's parapet fearlessly, pushed in the sand bags, making a large gap, greatly facilitating the entry of the remainder of raiding party. He worked continuously on improving the track back over 'No Mans Land' (Australian War Memorial, Australian Red Cross Society. Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau Files, 1914-18)

After this success the 7th moved back to camp until 5 October when they returned to the front near Hill 60. On 15 October both the 5th and the 7th battalions were on the move again, marching and on train and motor transports. On the 18th the battalions celebrated the 2nd anniversary of the sailing from Melbourne. Around the 25th the pattern of moving from place to place for both battalions ended at the Somme, where they were faced with terrible quagmires, rain, discomfort and general misery.

On 29 October both battalions marched out in preparation to relieve the British at the front line. The soldiers were fatiguing under the weight of equipment in the wet and muddy conditions, many suffering 'trench feet' - with no dry socks or boots to change into, feet stayed constantly wet leading to blisters and redness, resulting in skin tissue falling off (in the worst cases gangrene and permanent nerve damage would develop). The 7th moved into the front line at Gueudecourt on 1 November. On 6 November it was their time to be relieved, but so often it was this point at which troops were at their most vulnerable. And so it was on this occasion, enemy artillery inflicting many casualties: unfortunately this time Charles Cowan's number was up. When a colleague was wounded, Charles went to his aid, only to be shot and killed by a sniper. Eyewitness and secondhand accounts of the exact moment differ wildly. Consensus though is that Charles was hit in the abdomen, died shortly after, and was buried in a nearby trench. He had turned 21 just four days earlier.

The 5th battalion had been relieved from the front lines themselves the day before. The happiness from finally receiving a set of dry clothes would have been short-lived once the news reached Ken of his brother's death. Several months later (July 1917) Major Swift wrote to the boys' mother Florence Cowan back in Ascot Vale: "Your son was shot by a sniper who had just previously shot another officer, to whose assistance your son had gone, quite regardless of his own danger... Lieut. Cowan was one of the most popular officers in the battalion, and his work was exceptionally good. Just before his death he took part in a successful raid on the enemy trenches, and the officer in charge attributed a large measure of the success gained to the painstaking and thorough manner in which he carried out the important duties allotted to him." (Herald, 21 July 1917)

After another stint on the front lines, Ken's battalion had a period of training in Vignacourt from 18 November. On the 30th they went to Buire and served in the trenches there until 14 December. From there they moved to camp at Mametz where they remained in reserve. The first two weeks of 1917 were spent in Meaulte; later they marched to Albert and then past Bazentin to High Wood West camp, arriving on 25 January. Conditions were trying here, with lice very bad and the weather very cold. On 10 February, the 5th rejoined hostilities in France with a failed raid at Bayonet Trench. Inaccurate intelligence and a lack of artillery support gave them little chance; the troops were held up by a third row of wire and heavily bombed. Ken was one of many wounded, who had to be returned to safety under heavy fire: he suffered gunshot wounds to his right arm and leg. He was sent to the War hospital in Birmingham for treatment where he remained until 28 March.

A period of furlough was followed by a stint in the 66th battalion while continuing his recovery at Perham Downs. Transferring back to the 5th, Ken returned to France on 3 June, and rejoined his unit on 21 June. At this time the 5th battalion was having a well-earned break from the front lines at Henencourt Wood, and during this time erected a memorial at Pozieres. Ken had another medical setback in July with an outbreak of haemorrhoids that kept him out of action for over two weeks. He returned to his unit in late July, and on 1 August was promoted to Lance Sergeant.

On 8 August the 5th headed back toward the action in Belgium. The Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (which ran from July to November) was currently underway. The battalion spent time helping out with harvesting around their scattered billets, and came under occasional bombing. On 13 September they moved up to the front near Dickebusch, moving into battle on the 20th. A huge artillery bombardment preceded the attack and within a couple of days they had successfully taken Glencorse Wood. Ken distinguished himself in this battle and on 22 September he was promoted to Sergeant. Further acknowledgement was to follow on the 28th when he was nominated for the Military Medal for his work at Passchendaele:

This NCO displayed wonderful coolness in the operations east of Ypres on 20/23rd Sep, 1917. During the consolidation of the Blue Line and the subsequent heavy shelling which we sustained on the night of the 20th and the morning and evening of the 21st, whenever a shell burst in the Company Sector he would immediately run to the spot regardless of personal danger and assist in digging out buried men and tending casualties. His devotion to duty set a fine example to his comrades and at all times he could be relied upon to do his work in a thorough and earnest manner. (Australian War Memorial, Recommendation Files for Honours and Awards, AIF, 1914-18 War)

Following this success the 5th had withdrawn to Steenwoorde, but from 28 September moved back towards Ypres, which while now behind the front line, was still shelled and therefore unsafe. On the 30th they moved again to the front near Broodseinde, where they endured lots of shelling until 3 October. Ken sustained serious wounds to his legs and thigh and sadly died from those wounds the following day (4 November 1917). He was ten days short of his 24th birthday. He would not see his Military Medal, but when his mother was alerted to the honour, she requested it be sent to her. Upon receiving it, Florence wrote back, in April 1918:

I would like to write a few words of thanks for the medal you have sent on to me, it is needless for me to say how much we will all prize it especially as my dear boy did not live to receive it. He has received his reward Rest after over three years service. I cannot but be thankful that my two dear boys are safe at rest out of this present struggle now going on. God grant it may not be for very much longer & that a lasting peace may be established. (National Archives of Australia: B2455, First Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920)

The heartbreak Florence must have suffered with the loss of a second son must have been so painful, but you can see from the letter her positivity in the fact that they are suffering no more. Interestingly, there is future correspondence from Florence in the war file that shows a change to her address: shw writes it as 'Passchendaele, 19 Moonee St, Ascot Vale'. This is something I had not been aware of, and is a touching tribute to her son's sacrifice. Today, her boys are still remembered in Europe: Charles at the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France and Ken at the Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery in Belgium.

Footnote:

While Ken and Charles' younger brother Arthur was too young to serve in the Great War, he became a victim of the influenza epidemic which swept Australia following the war in 1919. He survived as Florence's only son (another brother Alfred had died as an infant in 1899) but remained a bachelor, meaning that today there is no-one left in the family named Cowan. Dad was always close to his grandmother Florence, and I think it is important that we never forget the devotion to duty, and ultimate sacrifice of Harry Kennett and Charles Davenport Cowan.

*If you are interested you can download historical footage of the Orvieto's departure in 1914 here: http://anzaccentenary.vic.gov.au/remembrance/hmat-orvieto-embarkation/index.html

Austin, Ronald J. Our Dear Old Battalion: the Story of the 7th Battalion, AIF, 1914-1919. Rosebud: Slouch Hat Publications, 2004.

Keown, A. W. Forward with the Fifth: a History of the Fifth Battalion, 1st A.I.F. Blackburn: History House, 2002.

Comments

Post a Comment